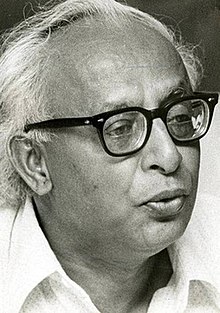

M. N. Srinivas

Birthday November 16, 1916

Birth Sign Scorpio

Birthplace Mysore, Kingdom of Mysore, British India (now in Karnataka, India)

DEATH DATE 1999-11-30, Bangalore (now Bengaluru), Karnataka, India (83 years old)

Nationality India

#51338 Most Popular