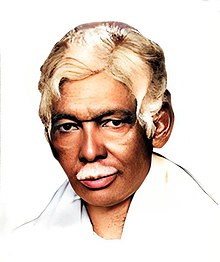

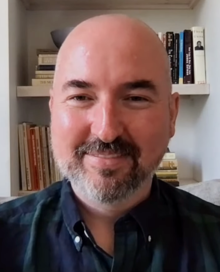

Herman J. Mankiewicz

Popular As Herman Jacob Mankiewicz (Mank, Manky)

Birthday November 7, 1897

Birth Sign Scorpio

Birthplace New York City, U.S.

DEATH DATE 1953, Los Angeles, California, U.S. (56 years old)

Nationality United States

Height 5' 10" (1.78 m)

#25391 Most Popular