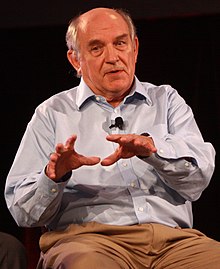

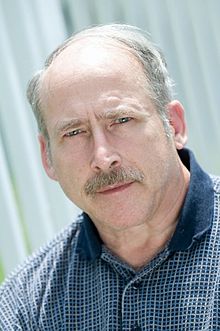

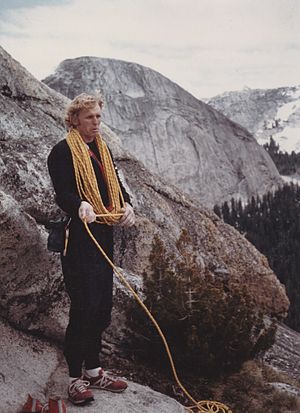

Charles Murray (political scientist)

#31725 Most Popular

1940

1943

1949

1950

1961

1965

1968

1974

1980

1981

1989

1990

1994

2012

2014